If ever one wanted to awaken a sleeping giant the Japanese in WWII could not have planned a more effective way to do it. We call that awakening the bombing of Pearl Harbor and we set aside December 7th each year in remembrance of the men and crew stationed at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and the atrocities and unprovoked attack waged by an enemy if we are found slumbering.

But the heaviest loss that morning came in human terms. More than 3,400 U.S. military casualties were suffered, including 2,335 killed, including 1,177 sailors and Marines killed on the U.S.S. Arizona. 1,102 of them remain entombed on their ship which remains at the bottom of Pearl Harbor. The attack was the impetus that caused the United States to enter World War II. There were also 103 civilian causalities with 68 of those dead.

By 09:30 hours the attack was over. The Japanese lost 29 aircraft along with their crews. This is a real testament to the Americans at Pearl Harbor. After having suffered a “sucker punch” sneak attack, they then attempted and rescued many men, tended to men and machinery, extinguished fires and made sense of a horrid battle zone, were then able to hone in on a quick moving enemy and take down 29 of the top Japanese air warriors.

The National War Museum supplies us with the following facts:

Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto conceived the Pearl Harbor attack and Captain Minoru Genda planned it. Two things inspired Yamamoto’s Pearl Harbor idea: a prophetic book and a historic attack. The book was The Great Pacific War, written in 1925 by Hector Bywater, a British naval authority. It was a realistic account of a clash between the United States and Japan that begins with the Japanese destruction of the U.S. fleet and proceeds to a Japanese attack on Guam and the Philippines. When Britain’s Royal Air Force successfully attacked the Italian fleet at Taranto on November 11, 1940, Yamamoto was convinced that Bywater’s fiction could become reality.

On December 6, 1941, the U.S. intercepted a Japanese message that inquired about ship movements and berthing positions at Pearl Harbor. The cryptologist gave the message to her superior who said he would get back to her on Monday, December 8. On Sunday, December 7, a radar operator on Oahu saw a large group of airplanes on his screen heading toward the island. He called his superior who told him it was probably a group of U.S. B-17 bombers and not to worry about it.

The entire attack took only one hour and 15 minutes. Captain Mitsuo Fuchida sent the code message, “Tora, Tora, Tora,” to the Japanese fleet after flying over Oahu to indicate the Americans had been caught by surprise. The Japanese planned to give the U.S. a declaration of war before the attack began so they would not violate the first article of the Hague Convention of 1907, but the message was delayed and not relayed to U.S. officials in Washington until the attack was already in progress. The Japanese strike force consisted of 353 aircraft launched from four heavy carriers. These included 40 torpedo planes, 103 level bombers, 131 dive-bombers, and 79 fighters.

The attack also consisted of two heavy cruisers, 35 submarines, two light cruisers, nine oilers, two battleships, and 11 destroyers. The attack killed 2,403 U.S. personnel, including 68 civilians, and destroyed or damaged 19 U.S. Navy ships, including 8 battleships.

The Greatest Generations Foundation (TGGF) has a battlefield return program where it assists combat veterans with the “opportunity to preserve their stories and find closure as they return to the hallowed grounds where they served and laid to rest those they lost in battle.” The TGGF says these are “sentimental programs” and “are often emotional” to the veterans. But, says TGGF they “provide veterans a measure of closure from their war experiences.”

In addition the TGGF sponsors veterans to tell their story of what happened and what they experienced at Pearl Harbor. Below are a few of the stories the TGGF has sponsored. This is a testimony to the valiant men who fought, bled, sacrificed and died at Pearl Harbor. Thank you gentlemen for defending America in the hour of her greatest need.

In this story we feature three veterans of Pearl Harbor and their testimony of that day.

79th Anniversary of Pearl Harbor Remembered

DONALD LONG

Kaneohe Bay Naval Air Station

Pearl Harbor survivor Donald Long, Kaneohe Bay Naval Air Station, was attacked five minutes before Pearl Harbor.

Biography: A member of the Barnum High School Class of 1939, Long started in the Navy in March 1941 after a stint in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in Tofte. By Dec. 7, he had been stationed at Kaneohe Bay Naval Air Station across Oahu’s island from Pearl Harbor.

Donald Long. Photo courtesy The Greatest Generations Foundation.

As Long tells it, that morning, he was assigned to be aboard one of the planes anchored in the bay. His watch began at 7:45 a.m. that morning when he was dropped off at the PBY (aka the Catalina Flying Boat). Just before 8 a.m., he was looking toward the shore for the signal lights when suddenly he heard aircraft flying nearby and the sound of explosions. He initially assumed it was the Army Air Corps out for some Sunday morning practice runs. He learned quickly that he was wrong.

“The sequence of events over the next few minutes is not entirely clear,” he said. “I saw aircraft flying over the hangars and explosions and fires on the ground. Moments later, a plane anchored near mine began to burn violently after being strafed. (The old aircraft fuel tanks were not ‘bulletproof’ and the fuel leaked out and was ignited by the shells.) Seconds later, one of the attacking planes made a run in my direction.”

Long bolted from the pilot’s seat and went to grab a life jacket as the bullets hit his plane.“I remember seeing little water fountains shoot up as the machine gun bullets went through the bottom of the plane,” he said. “They hit the wing tanks, too, and almost immediately, the entire plane was engulfed in flames – with me in the middle of the fire. At this point, I know I thought, ‘Get out!’ and I dashed toward the rear exit through the flames with no more thoughts of a life jacket.”

He dove into water covered with burning gasoline. Luckily, Long could swim.

“We were taught to swim through fire on the water during boot camp,” he said. “I don’t recall being burned, but I found out later that I was. I was aware of how difficult it was to swim with my shoes on — heavy, high-top, regulation work shoes.”

When he got 15 to 20 yards from the plane, Long went underwater and removed his shoes. In the meantime, the attacking planes made one or two more runs on the aircraft he’d been guarding, and the seaplane, with its wingspan of 100 feet, quickly sank.

Only two or three minutes had passed since the attack began, but when Long looked around, the hangars and planes on shore were all burnings. The aircraft on the water were either burning or had sunk.

“The attacking planes were low enough so I could see the rising sun markings [of Japan] and I must have realized we were under attack, but my first thoughts were of my well being because I was still floundering out in the bay some 1,000 to 2,000 yards from shore,” he wrote in an account of the day.

He spied a channel marker about 100 yards away and swam over to it. A triangular structure anchored to a thick wooden base about four feet square, he climbed on top and spotted a boat that was out looking for survivors. They took him back to shore, where Long was greeted by shipmates who had thought he was a goner.

Long was the only survivor of the three planes that had been in the water he found out later. And while only 20 died at Kaneohe Bay — a reasonably small Navy base — that morning, the assault claimed the lives of more than 2,500 people, wounded 1,000 more, and damaged or destroyed 18 American ships and nearly 188 airplanes, according to the history.com website.

“I was told I looked pretty bad,” said Long, who was awarded a Purple Heart medal for his injuries in the line of duty. “My head, face, and arms were burned, and I suppose the oil and saltwater didn’t help my appearance. I was taken to sickbay where, by comparison to other survivors, I was in perfect health.”

After being treated and bandaged, Long was back on the job the same morning to guard against possible Japanese landing parties. A day or two later, he was pictured in a Duluth newspaper as a local boy who survived the attack that shocked the nation. The oldest of Bert and Anna Long’s six children, the news that he survived the attack was greeted with much relief by family and friends at home in Minnesota.

Today, Mr. Donald Long resides in Napa, California, and enjoys traveling and sharing his wartime experiences.

RICHARD CUNNINGHAM

USS West Virginia BB-48. Photo US Navy Archives.

Pearl Harbor survivor Seaman 1st Class Richard Cunningham recalls the Japanese Attack from the USS West Virginia.

Cunningham is a retired aerospace industry employee who has spent most of his life in Texas. He grew up in Irondale, Ohio, the eldest of four. His father, a veteran of WWI, worked in a brickyard, and the family lived in the back of a grocery store during the dark days of the Depression. Cunningham learned to fish and hunt rabbits and groundhogs.

Richard Cunningham. Photo courtesy The Greatest Generations Foundation.

After graduating high school, one of Cunningham’s buddies, nicknamed Little Joe, pestered him to join the Navy. “He asked me one time too many times.” He told Little Joe, “Let’s go!”

A steady military paycheck attracted Cunningham. They enlisted in Youngstown. They trained at the Great Lakes Naval Station near Chicago and then went separate ways. Cunningham shipped off for duty on the 623-foot-long USS West Virginia, commissioned in 1923 and still the nation’s newest battleship. It was being refurbished at the naval shipyard in Bremerton, Washington. Cunningham’s first job was to scrape barnacles off the sides of the ship. In late 1940, it relocated to Pearl Harbor with the rest of the Pacific fleet.

On the morning of December 07, shortly sunrise, Seaman 1st Class Richard Cunningham and two other sailors, Earl Kuhn and Bill Morris boarded a wooden boat tethered to their battleship, the USS West Virginia. They got underway at 7:50 a.m. and motored across the placid water. Theirs was a most routine assignment that morning: cross the harbor to a dock near the officers’ club where several officers waited for a pick-up.

Despite all the talk of an impending war, crews were not on high alert. December 7 was a Sunday, and Sundays were leisurely. Sailors were at ease. Officers slept on shore. Some men nursed hangovers from a Saturday night in Honolulu; others gathered for Sunday morning services topside. Watertight hatches and doors on the big warships–compartments designed to confine damage and flooding to a small area in an attack–were open.

The day before, Cunningham took shore leave and shopped for a Christmas gift for his mother. He bought her a cameo brooch, which he stored in his locker beside his bunk on deck.

After a restful night’s sleep, Cunningham was dressed in his Navy whites and stood on the boat’s wooden deck to enjoy the cool breeze. Looking across the smooth water, he held onto the sparkling brass railing, shiny from the endless hours of polishing by Cunningham and the crew.

Suddenly, the calm was shattered by loud sounds and the sight of torpedo bombers swooping down directly overhead and skimming the water’s surface. Cunningham found himself with a front-row seat to one of history’s most significant events—the Attack on Pearl Harbor.

Cunningham remembered looking up and recognizing the red discs on the Japanese torpedo bombers’ sides, discs sailors called big red meatballs.

“At 7:55, we’re right here, and we’re facing these torpedo planes,” Cunningham said, pointing at the spot on a map he had carefully written “the path of our boat on 12-7-41.”

“There was a big blast, and we saw those two meatballs, and we said to ourselves, ‘This is it! This is it. Those are Japanese, and we’re at war. This is no training. This is no drill.’ ”

“One after another, we’re facing these torpedo planes. You’d look up and see these guys, and they’re grinning from ear to ear. They had the machine gunner behind them. But the pilot of our boat, Earl Kuhn, kept that boat right underneath these Japanese torpedo planes. The planes were dropping torpedoes, which were running under and beside our boat. But he kept it there because had we cut and run, I wouldn’t be talking to you now because the machine gunner would have got us. We’re right underneath, and the machine gunner can’t shoot down.”

Alarms and general quarters announcements sounded, calling all sailors on ships and airmen at Hickman and other airfields, to battle stations. In four minutes, Cunningham witnessed one of the first American shots of the war. Two sailors on the USS Sumner, a survey ship moored at a nearby submarine base, fired its World War I-era guns. They hit one of the planes point-blank.

“There was a ball of fire so close that it singed my eyebrows and the hair on the back of my hands,” Cunningham said, wide-eyed, remembering the scene. “And the plane just disappeared. The ball of fire just melted it. And the propeller went spinning toward Kuahua [a peninsula that housed a new supply depot].”

Cunningham served the rest of the war, helping to run supply and troop ships that sailed into battles across the Pacific, including Guadalcanal, the Treasury Islands, New Georgia, Rendova Bougainville. He fired a machine gun at Japanese diving planes in one fight, his bare feet on the ship’s railings to avoid hot shell casings that littered the deck. Another night, near New Georgia, his boat struck a reef and all but sank. Some coral kept its bow out of the water, and he and his shipmates huddled there and clung for life. They were rescued by a U.S. minesweeper the next day.

After the war, he had a brief marriage and a long one and four daughters. He moved to Texas and worked in the aerospace industry. He wrote and prepared engineering and performance documents on F-111 fighter jets for General Dynamics in Fort Worth.

Today, he lives in Hewitt with his wife, Patty, and still receives many invitations to speak about Pearl Harbor.

J.C. ALSTON

Pearl Harbor survivor J.C. Alston, a young Texas Boy at Pearl Harbor.

_after_turrets.jpg&f=1&nofb=1)

USS California BB-44. Photo US Navy Archives.

Alston was born March 3, 1923, in Cone, a hamlet about thirty-five miles northeast of Lubbock. The middle of seven children in a farming family grew up during the bitter dust bowl years on the Southern Plains. He remembers when electricity came to the community, and they began using light bulbs instead of kerosene lanterns. Alston was a young teenager when his parents hung up their plow and moved to Temple in Central Texas. His father became a carpenter.

On the morning of Dec. 07, eighteen-year-old J.C ALSTON was woken shortly before 4 a.m. on December 7, 1941, a fellow sailor awakened J.C. Alston as he slept in a bunk on the USS California, the lead ship moored to docks adjacent to Ford Island in the middle of Pearl Harbor. It was Alston’s turn to take up watch on the port side of the battleship’s quarterdeck. His shift was from 4 a.m. to 8 a.m.

After waking the officer of the day and the chief boatsmate, Alston stood under a clear dark sky filled with stars and a waning moon. He could see the silhouette of the battleship’s coning tower and its gun batteries. The crew was always to awaken the captain if they saw any threat, but the eighteen-year-old sailor had never needed to awaken him.

Sometime around sunrise, the bugler sounded reveille. The harbor water was so glassy smooth that Alston watched a PBY pontoon plane repeatedly fail to take off from the surface of the harbor’s waters. (PBY is short for “patrol bomber” with the “Y” the military designation for its manufacturer, Consolidated Aircraft.) Needing choppier water to get lift, a PT (patrol torpedo) boat cruised in circles to create a wake, and the seaplane was soon aloft. On the forward deck, sailors put up a white awning for Sunday morning religious services. Small boats arrived with GIs planning to attend. His shift nearly over, Alston was ready for the next sailor to relieve him. He was hungry for breakfast.

He then heard the aircraft’s noise flying in his direction and saw low-flying planes coming from behind a mountain on Oahu. “I didn’t know they were Japanese at the time. I thought some aircraft carriers were training,” Alston said, remembering that the USS Lexington left the harbor the night before, laden with planes.

“Those are Japanese planes!” the boatsmate yelled. “Japanese planes!”

The bugler sounded general quarters calling sailors to their assigned battle stations. Alston’s heart raced as he ran to his, the number two 14-inch-diameter gun on mid-deck, and slid inside its turret. He was a gun loader. He could hear a barrage of sounds from his darkened space – roaring planes, machine-gun and anti-aircraft fire, sirens. He felt the ship violently rock when torpedoes below its waterline hit it.

J.C. Alston. Photo courtesy The Greatest Generations Foundation.

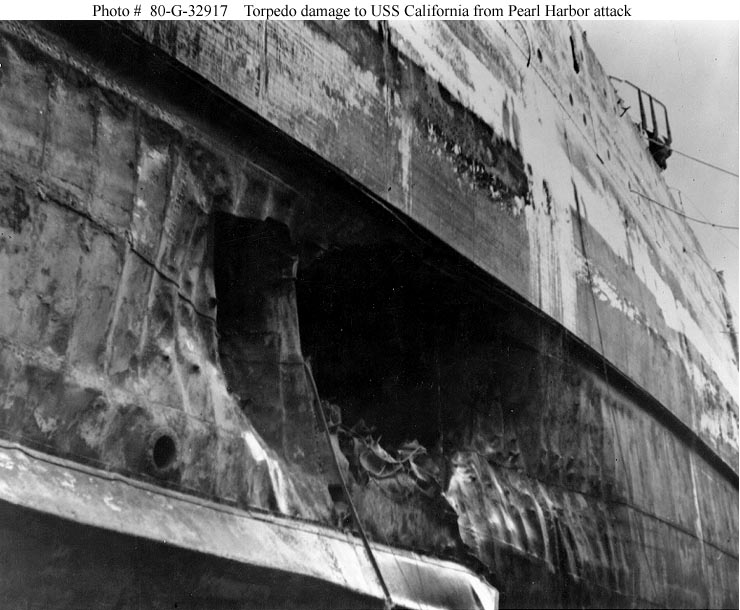

According to the action reports filed after the attack, California was struck by two torpedoes on its port side at 8:05 a.m. and then blasted by another fifteen minutes later. At 8:10 a.m. Alston heard the loudest explosion: The bomb that blew up the USS Arizona. Blinding smoke filled the sky, and fire lapped the water.

Alston’s ship was nearly hit by four bombs that caused serious flooding, and at 8:30 a.m., a bomb penetrated to its second deck, where it exploded and sparked a tremendous fire that killed about fifty men.

“Fire was everywhere,” Alston recalled. The listing ship was ordered abandoned because of the threat that it would blow up. Alston emerged from his turret and joined other sailors to leap from the quarterdeck and swim about twenty yards to nearby Ford Island. Drenched and wide-eyed, the boys were partially hidden by smoke, but they could see Japanese planes bombing and strafing. They seemed close enough to throw a rock and hit the low-flying aircraft, which swooped down and then pulled up at the last second to avoid the towers of the burning battleships. “There were so many I don’t know how they missed each other. They were like a bunch of bees,” Alston said.

On Ford Island, officers mustered their men for roll calls to see who was still alive or missing. Soon, Alston and other sailors were ordered back aboard to operate California’s guns that remained above water. This time they scrambled across timbers that had been laid across to the quay, climbed a ladder, and pulled themselves on board.

USS California BB-44. Photo US Navy Archives.

In an almost comical confusion of combat, another abandon ship order came minutes later as the ship continued to sink despite valiant efforts to keep her afloat. The inrushing water could not be isolated, and California settled into the mud with only her superstructure above the water.

“Anybody who says they weren’t scared, well, they’re just not quite telling the truth,” Alston said as he told his story in the living room of his home in Troy, Texas. “Of course, it hits them after it’s over more than it did at the time.” Roughly one hundred of California’s crew died, and sixty-one were wounded.

Later in the war Second Class Petty Officer Alston saw action in Leyte’s invasion in the Philippines and action at Iwo Jima. On September 2, 1945, Alston was on the West Virginia’s deck in Tokyo Bay. Japanese officials joined Admiral Chester Nimitz, General Douglas MacArthur, other allied commanders on the nearby USS Missouri to sign the instrument of surrender, officially ending the war weeks after the United States dropped atom bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Alston was discharged in October and returned to Texas. He drifted to Lubbock, where he helped a relative harvest wheat and then returned to Temple and landed a job as a truck driver at a Veterans Administration hospital. In 1949, he married a local girl, Arita June, and they had two daughters. He remained at the VA for thirty-four years in various positions, including as fire department crew chief and supervisor of laundry service.

Many years before Alston was able to forgive the Japanese, it took many years, but ignore he has. The widower often tells his story to schoolchildren and attends veterans’ reunions and events. He has returned to Pearl Harbor many times with The Greatest GENERATIONS Foundation.

This past summer, in a touching scene in Texas, a resident threw a drive-by parade to celebrate J.C. Alston 97th birthday.

You may find more of their stories at The Greatest Generations Foundation.

We have a few WWII veterans scattered around us. They’re older now and perhaps don’t move quite as fast, but they have knowledge, and have seen and experienced what few have today. And all of them from the same era. Take time to thank a veteran, and perhaps hear a story from the Greatest Generation. You’ll be glad you did.

Please “like”, comment, share with a friend, and donate to support The Standard on this page.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

Trackbacks/Pingbacks